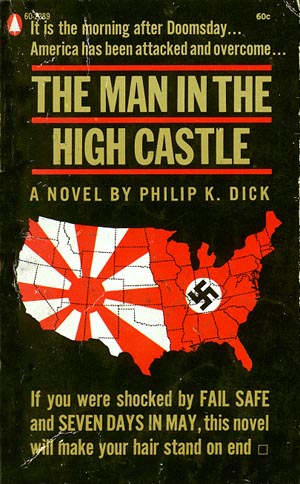

An interesting thing happened at the end of Philip K. Dick's Man in the High Castle that I thought fellow lean-sippers might enjoy. The setting of the novel, as you might presume, is the west coast of the U.S. in an alternate-history 1962, controlled by the Japanese after the Axis powers won World War II. An nice enough concept that helped usher in an already developing alternate-history sub-genre of SF at the time. It's an approach that holds some pretty immediate interest for people with a historical imagination, but there's a certain level of gimmickry involved, in that when a book banks on a fascinating setting it often belies a less-than-solid story. If you're like me you've probably read enough bad speculation (and made enough bad speculation) to scrape the varnish clean off the entire idea of "imagining what it would be like!"

Anyway our mutual friend Phil manages to put it down quite nicely. I should mention, before I talk about the end, that throughout the book there are constant inner monologues where white people think about being a minority in a Japanese controlled environment. It's unusual and a good example of the 'trading places' dynamic the book is supposed to engage with. If I were, say, teaching a class on race I'd provide some passages from this book as catalysts for discussion.

To the ending. Running throughout the novel is a notorious book, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, which is banned in German controlled parts of the world but available in Japanese controlled parts and printed in neutral areas.The novel describes a world in which the Axis powers lost the war. The author, Hawthorn Abendsen, is the title's "man in the high castle," and in the final pages of the book one of our main characters tracks him down as asks him about the novel. Also running throughout the book is the I Ching, which countless characters rely on to guide them during times of confusion. Dick reportedly used it himself to write the novel, and I have no doubt he referred to it as 'The Oracle" in the same reverential way the book's characters do.

Ultimately what happens is that several characters consult the I Ching on the meaning of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. The response they get is simple: the book is true. The Axis powers didn't win the war and the U.S. stayed a sovereign nation. Which seems simple because for the reader (us) that's the case. The problem is that Abendsen's novel doesn't describe what actually happened in our world, but rather another alternate history appropriate to the world of the book. The only supposition you have to make is that somewhere within Abendsen's book he wrote in the equivalent of himself, someone writing an alternate-history novel about how the Axis powers actually did win. The white lines separating Abendsen's author's alternate history from his own and from Dick's alternate history suddenly become purple and start to melt away, reaching further to suggest that our own history could radically appear quite "alternate." In the same way that it does for the characters at the end of High Castle. Anyone who takes the study of history seriously knows it's a malleable thing, that the past comes down almost entirely to representation by the present. If you take the implications of High Castle's ending seriously (which, for the brief moment where you're reading it, you should) then you'll find the same sweet, slight, fleeting but potent traces of drank on your lips that you did when you read the lines

"All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players."

or when you tried to live life normally for the first hour post-watching-eXistenZ.

1 comment:

For a great listing of "book-in-book" check out the inactive Invisible Library at

http://invislib.blogspot.com/

Post a Comment